Geo, our solution for read-only mirrors of your GitLab instance, started with our co-founder Dmitriy Zaporozhets’ crazy idea of making not only the repositories, but the entire GitLab instance accessible from multiple geographical locations.

At that time (Q4 of 2015) there were only a few competitors trying to provide an automatic mirroring solution for repositories and/or issue trackers, and they were mostly built around an additional independent instance and a bunch of webhooks to replicate events. Also, in those cases, no other data was shared outside this asynchronous replication channel, and you had to set up the webhook per project and take care of the users yourself. Long story short: this was not practical for any instance with more than a couple of projects.

We also had a previous experience early that year using DRBD to migrate 9 TB of data from our dedicated co-location hosting to the AWS cloud, which didn't provide the scale, performance, or the UX we had in mind for the future.

Here's the history of how we built Geo:

Phase 1: MVP

Geo's first mission was to provide people who were located in satellite offices, or in distant locations, with fast access to the tools they need to get work done. The plan was not only to make it faster for Git clones to occur in remote offices but also to provide a fully functional read-only version of GitLab: all project issues, Git repositories, Wikis, etc. automatically synchronized from the primary with as little delay as possible.

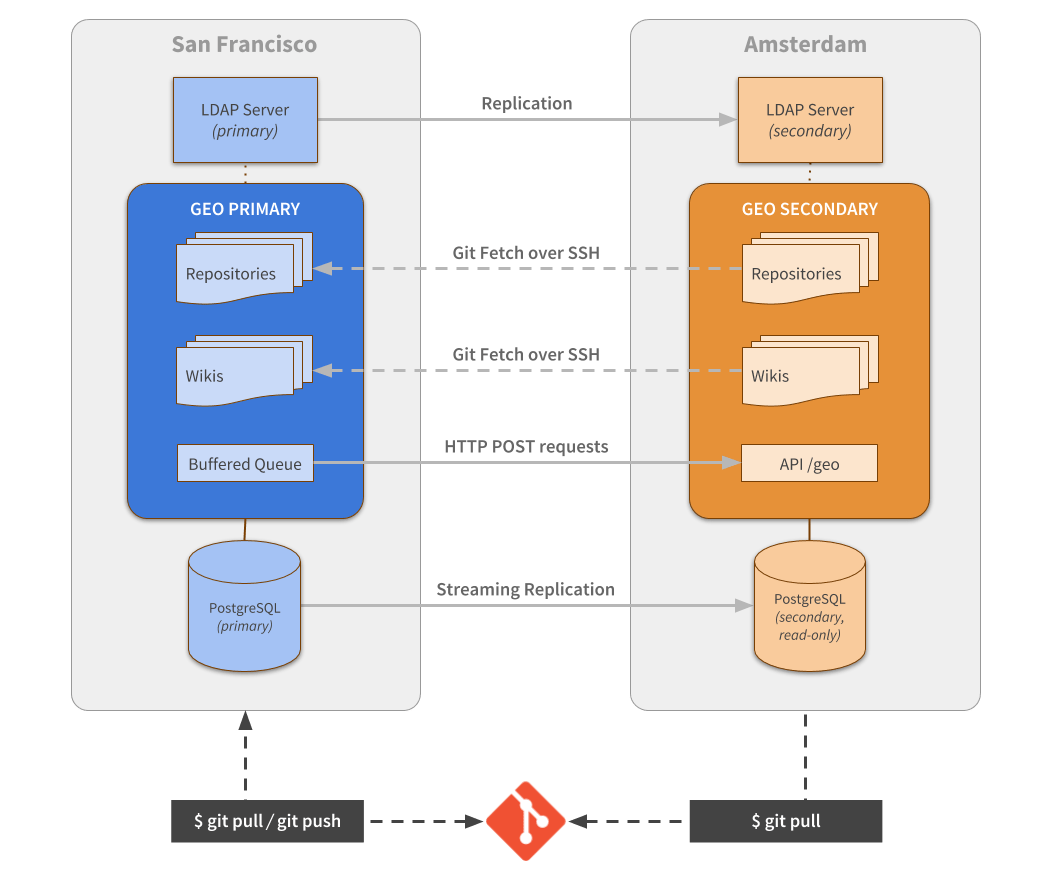

To get there we made a few architectural decisions:

1. Use native database replication

This would allow us to replicate any user-visible information, user content, user and permissions, projects, any project relation to groups/namespaces, etc. Basically, any data ever written to the database in the primary node made readily available to the others, without any extra communication overhead in the webhooks.

It is also the most Boring Solution, as it uses proven technologies developed for databases in the past two decades. To simplify the endeavor we decided to support only PostgreSQL.

2. Use API calls to notify any secondary node of changes that should happen on disk

This is the second synchronization mechanism. If a new project is created or a repository updated, this notification lets any other node know they have this pending action, and should replicate the new data on disk.

3. Use Git itself to replicate the repositories

We investigated many alternatives to replicate our repositories, from using basic UNIX tools (like rsync or equivalent) to specific distributed file-systems features. We were aiming for a simple solution, as ideally we had to support the lowest common denominator, which is a Linux machine running the default filesystem (ext3 or 4). That limitation ruled out any distributed file-system based implementation.

We considered rsync and its variants as well, which could potentially work for our use case, but that would add significant CPU for each synchronization operation, and we expect it to increase as the repositories get bigger and bigger.

By using rsync we would need to grant more on-disk permissions than we were comfortable doing, and restricting its reach could be an engineering challenge in itself.

The same can be said for scp and its variants. In the end, we decided to use Git itself and benefit from its internal protocol. This was a no-brainer and very easy decision to make. We understood the protocol enough and we already had the required safeguards in place. All we needed was a slightly different authentication mechanism for the node-to-node synchronization.

4. Always push code to the primary, pull code from anywhere

When we started Geo, there was no bundled Git support for having a multi-repository "transactional" replication, or information on how to implement one.

We figured out quickly that to implement something on that line it would require either a global lock or to implement a variant of RAFT/PAXOS on top of Git internal protocol.

Both solutions have their downsides and tradeoffs, and adding to that the time and effort to build it correctly, led us to opt for the simplest implementation: always push to the primary, notify secondaries that repository data changed, and have the secondaries fetch the changes. This is also in line with our motto of Boring Solutions.

The initial repository synchronization is no different than doing a git clone <remote> --mirror. The same idea goes for the repository updates, they behave very similarly to a git fetch <remote> --prune. The difference is that we need to replicate additional, internal metadata as well, that is not normally exposed to a regular user.

5. Don’t replicate Redis data between nodes

We initially thought we could replicate Redis as well as the main database in order to share cached data, session information, etc. This would allow us to implement a Single Sign-On solution very easily, and by reusing the cache we would speed up the initial page load.

At that time Redis only supported Leader to Follower replication mode and even though it is usually super fast when used in a local network, the fact remains that replicating data across disparate geographical locations can add significant latency.

This additional latency would impact on the initial objective of simplifying the Single Sign-On implementation. If you simply log in on the primary node and get redirected to the secondary, chances are that the session information would still not be available on the secondary node due to the replication latency.

That would eventually fix itself by redirecting back and forth, but if the latency is significant enough, your browser will terminate the connection based on the redirect loop prevention feature. Another downside of this approach is that it creates a hard dependency on the primary node being online, or otherwise the secondary node would be inaccessible and/or completely broken.

In addition to all these issues, we needed an additional Redis instance that supports writing data to it, in order to persist Jobs to our Jobs system on the secondary node.

So it made sense, in the end, to give up on the idea of replicating Redis, and we started looking for a solution to the authentication problem.

6. Authenticate on the primary node only

Because we can’t write on the main database of secondary nodes, any auditing logs, brute force protection mechanism, password recovery tokens, etc. can’t have their data and state persisted inside secondary nodes. The only viable solution then is to authenticate on the primary and redirect the user to the secondary.

This decision also helped with the integration of any company-specific authentication systems. If a company uses internal authentication based on LDAP, CAS or SAML for instance, then they wouldn't have to replicate that system to the other location or configure firewall rule exceptions to accept traffic over the internet.

7. Implement Single Sign-On and Single Sign-Off using OAuth

With the previous Redis limitations in mind, we looked into alternatives to implement the authentication. We had to choose between either CAS or an OAuth-based one. As we already had OAuth Provider support inside GitLab, we decided to go with that.

Basically, for any Geo node configured in the database we also have a corresponding OAuth application inside GitLab, and whenever a new user tries to log into a Geo node, they get redirected to the primary node and need to "allow" the "Geo application" to have access to their account credentials at the first login.

The shortcoming here is that if you are not logged in already and the primary goes down, you can't log in again until the primary node connectivity issue is fixed.

8. Build a read-only layer on the application side to prevent accidents

We needed this safeguard in place in case any required subsystem was misconfigured. With the read-only layer, we can prevent the instance from diverging from the primary in a non-recoverable way. It's also this layer that prevents anyone from pushing a repository change to the secondary node directly.

9. Don’t replicate any user attachments yet, just redirect to the primary

Instead of trying to replicate user attachments at this stage, we decided to just rewrite the URLs pointing the resource to the primary node instead. This allowed us to iterate faster and still provide a decent experience to the end users.

They would still enjoy faster access to the repository data and have the web UI rendering the content from a closer location, with the exception of the issue/merge request attachments, avatars etc, which were still being fetched from the primary. But as they are also highly cachable the impact is minimal.

This was the initial foundation that allowed us to validate Geo as a viable solution. Later on, we took care of replicating the missing data as well.

Bonus trivia

The term Geo came only after a while, it was previously named as GitLab RE (Read-Only Edition), followed by GitLab RO (Read Only) before getting its final name: GitLab Geo.

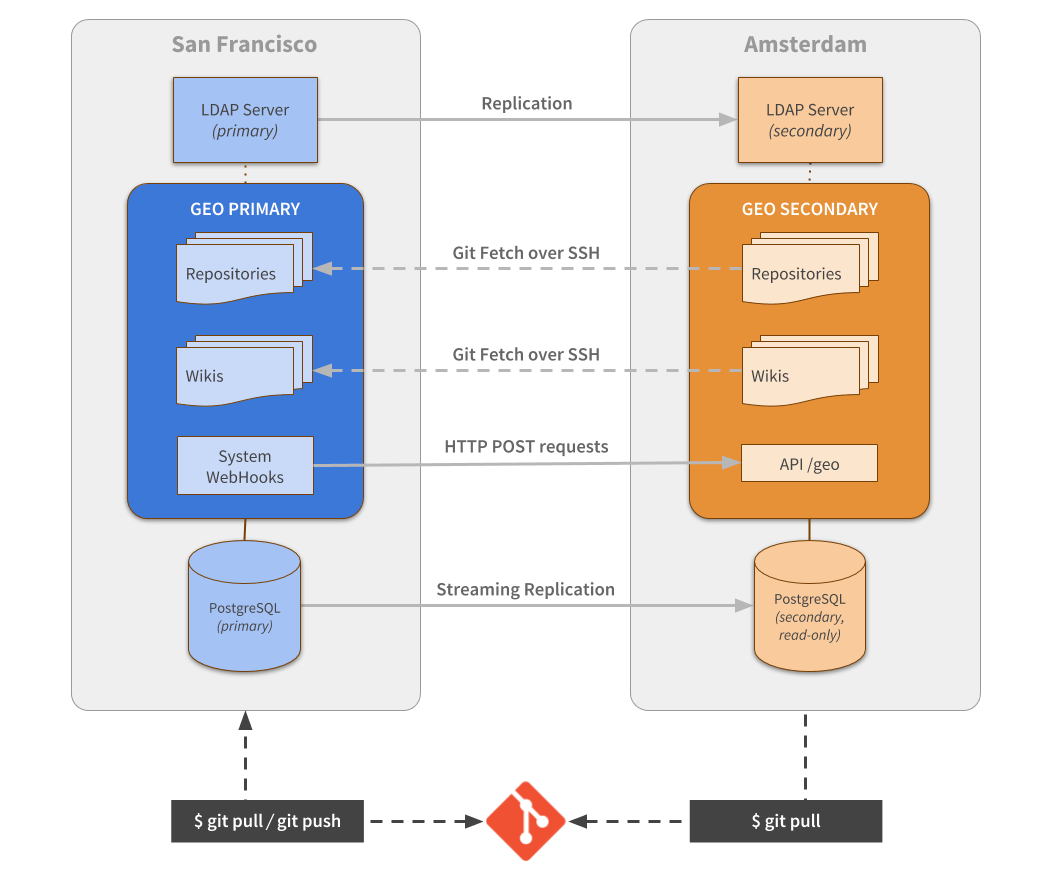

Phase 2: First-generation synchronization mechanism

With the MVP implementation done, we needed to pave the way for a stable release. The first part we decided to improve was the notification mechanism for pending changes. During the MVP, we built a custom API endpoint and a buffered queue. That queue was also optimized to store only unique, idempotent events. If a project received three push events in the last few seconds, we only needed to store and process one event notification.

We decided that instead of building our own custom notification "protocol" and implementing some early optimizations, we should leverage existing GitLab internal capabilities: our own webhooks system.

By taking that route, we would be forced to "drink our own champagne" and as a result, improve our existing functionality. That decision actually resulted in improvements to our system-wide webhooks in a few ways. We added new system-wide webhook events, expanded the granularity of the information available, and fixed some performance issues.

We've also improved the security of our webhooks implementation by adding ways of verifying that the notification came from a trusted source. Previously the only way to do that relied on whitelisting the originating IP address as a way to establish trust.

This security limitation was not present in the MVP version, as we reused the admin personal token as the authorization mechanism for the API, which is also not ideal, but better than previous webhook implementation.

I consider this to be the first generation of the synchronization mechanism that was used in the wild. It had a few characteristics: it reacted almost like real-time for small updates, webhook was fast enough and parallelizable to be used on the scale we wanted to support.

As the very first version of Geo was only concerned with getting repositories available and in-sync, from one location to the other, that's where we focused all of our efforts. At that time, setting up a new Geo node required an almost identical clone of the primary to be available in advance. That included not only replicating the database but also rsyncing the repositories from one node to the other. For improved consistency, we required initially a stop the world phase in order to not lose changes made during the time between when the backup started and when the secondary node got completely set up.

While this was still closer to a barebones solution, it already provided value for remote teams working together in a shared repository or simply in any project that needed to synchronize code between different locations. We had a few customers trying it out and evaluating the potential, but it was still not ready for production use as we were still missing a lot of functionality.

The stop the world phase previously mentioned got phased out later with the help of improved setup documentation. Much later, a good chunk of the initial cloning step got simplified by leveraging some improvements in the next-generation synchronization and by introducing a backfilling mechanism.

First-generation synchronization pitfalls

While our first-generation solution worked fine for the highly active repositories, the use of webhooks as a notification mechanism had some really obvious drawbacks.

If, for any reason, the notification failed to be delivered, it had to be rescheduled and retried. Also because we were using our internal Jobs system to dispatch the webhooks, having a node go dark for a few hours meant our Jobs system would be busy retrying operations over an unreachable destination for at least that same amount of time.

Depending on the volume of data and how long it has been accumulating changes, that could even fill up the Redis instance disk storage. If that ever happened we would have to resync the whole instance again and start from scratch.

We've improved the retrying mechanism with custom Geo logic to alleviate the problem, but it was clear to us that this was not going to be a viable solution for a Generally Available (stable) release.

Also because of backoff algorithm in the retrying logic, in conjunction with the asynchronicity aspect of the system, it could lead to important changes taking a lot of time to replicate, especially in less active projects. The busiest ones were less affected, as any update to the repository would get it to the current state rather than to the state when the update notification was issued. And because the project is receiving many updates during the day, it's expected to generate also many notification events.

Any implementation misstep between sending the webhook or receiving and processing it on the other side could mean we would lose that information forever. This was again not a major issue with highly active projects, as it would eventually receive a new, valid update notification which would sync it to the current state, but the outliers could miss it until someone notices or another update arrives much later.

We also wanted to make Geo a viable Disaster Recovery solution in the long term, so missing updates without a way to recover from it was not an option.

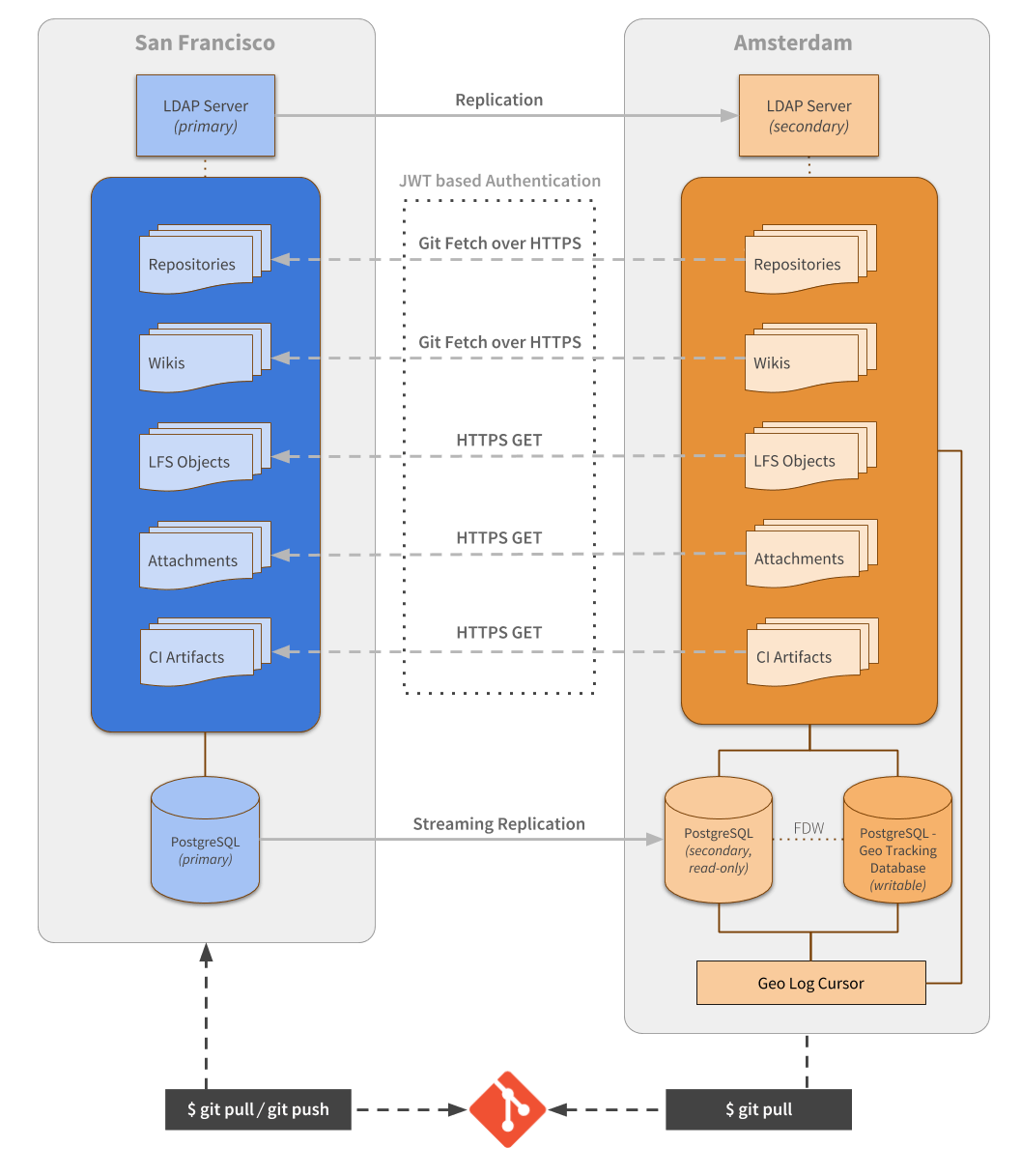

Phase 3: Second-generation synchronization mechanism

We started looking for alternative ways of notifying the secondary nodes and also considered switching to other standalone queue systems instead. We were also worried about the lack of control over the order in which the operations would happen in a parallel and asynchronous replication system and on the effect it had on the data on disk.

A few examples of situations that can happen because of the parallelism and the async nature of it:

- A project removal event can be processed before a project update for the same repository

- Renaming, creating a project with the new name and sending new content to it, if processed in an incorrect order, can lead to temporary data loss

There was also the case when the notification arrived before the database had replicated the required data. As an example, when the node receives the notification for new project creation, but the database doesn't have it yet.

That required the secondary node to keep a "mailbox" until the received events are ready to be processed. As they were basically Jobs, that meant keep retrying until the job succeeded.

Considering all the complexity we had brought to the application layer, we investigated a few standalone queue systems to which we could offload the burden, but decided ultimately to build an event queue mechanism in PostgreSQL instead, as it had three important advantages:

1. No extra dependencies

We were already replicating the database, so there is no need to install, configure and maintain another process, worry about backing up yet another component, integrate it in our Omnibus package, and provide support for our users.

2. No more delayed processing

If the event arrives on the other side, the data associated with it will already be there as well. We can also guarantee consistency with transactions and repeat less information than with the webhooks implementation.

3. Easy to retry/restore from backup or in a disaster situation

With a standalone queue system, to have a consistent backup solution you either need some sort of WAL files that could help rebuild a consistent state between the systems or do backups in a "stop the world" way, otherwise, you may lose data.

Our implementation

We took inspiration from how other log-based replication systems work (like the database) and implemented it with a central table as the main source of truth and a few others to hold bookkeeping for specific event types. Any relevant information we used to ship with the webhook notification is now part of this implementation, with extras to support the missing replicable events.

On the secondary node, these new tables are read by a specific daemon (we call it the Geo Log Cursor), and as the name suggests, it holds a persistent pointer of the last processed event. This allows us to also report the state of replication and monitor if our replication is broken. We also made it highly available, so you can boot up one as Active and keep a few extras as Standby. If the Active daemon stops responding for a specified amount of time a new election starts and one of the Standbys takes place as the new Active.

The second part of the new system requires a persistent layer on the secondary node to keep any synchronization state and metadata. This was done by using another PostgreSQL instance.

We couldn’t reuse the same main instance, as we were replicating with Streaming replication mode. With Streaming replication, the whole instance is replicated, and you can’t perform any change in it. The alternative to being able to replicate and write in the same instance is to use Logical replication mode, but at that time, there was no official Logical Replication support available in the PostgreSQL versions we supported (PgLogical was also not a viable alternative back then).

With the new persistence layer (we call it the Geo Tracking Database), we had the foundations built to be able to actively compare the "desired vs actual" state, and find missing data on any secondary instance. We built a more robust backfilling mechanism based on that as well.

Querying between the two database instances (the replicated Secondary, and the Tracking Database), were made much faster and scalable by enabling Postgres FDW (Foreign Data Wrapper). That allowed us to query data using a few LEFT JOIN operations among the two instances, instead of pooling with multiple queries from the application layer against the two databases in isolation.

Other improvements

Another important shortcoming fixed was how we replicated the SSH Keys. This was technical debt we needed to pay since the first implementation. Historically, GitLab built the SSH authorization mechanism as with many other Git implementations, by writing each user-provided SSH Key to the AuthorizedKeys file on the server and pointing each one to our gitlab-shell application.

This implementation allowed us to authenticate the authorized users, and because we control how the Shell application is invoked, we can pass a specific key ID to it, that can be used later to identify the user on our database and authorize/deny operations to specific repositories.

The problem with this approach, in general, is that the bigger the user base is, the slower the initial request will be, as OpenSSH will have to perform a scan to the whole file (O(N) complexity). With Geo, that's not just about speed but any delay in updating this file either to add a new key or to revoke an existing one is very undesirable.

When we decided to fix that we did for both Geo and GitLab Core by using an interesting feature present in newer versions of OpenSSH (6.9 and above), that allows overriding the AuthorizedKeys step, switching from reading the keys from a file to invoke a specified CLI instead (O(1) complexity). You can read more about it in the documentation here.

We fixed another shortcoming around the repository synchronization, switching from Git over SSH protocol, to Git over HTTPS. The initial motivation was to simplify the setup steps, but that decision also allowed us to shape the synchronization differently when it was originated from a Geo node, vs a regular request. Internally we store additional metadata in the repository and also commits that may no longer exist in your regular branches, but were part of a previous merge request, or had user comments associated with them.

By also switching to full HTTP(S), it made it simpler to run our development instances locally with GDK, which helped to improve our own internal development process as well.

Phase 4: Third-generation synchronization and the path to a Disaster Recovery solution

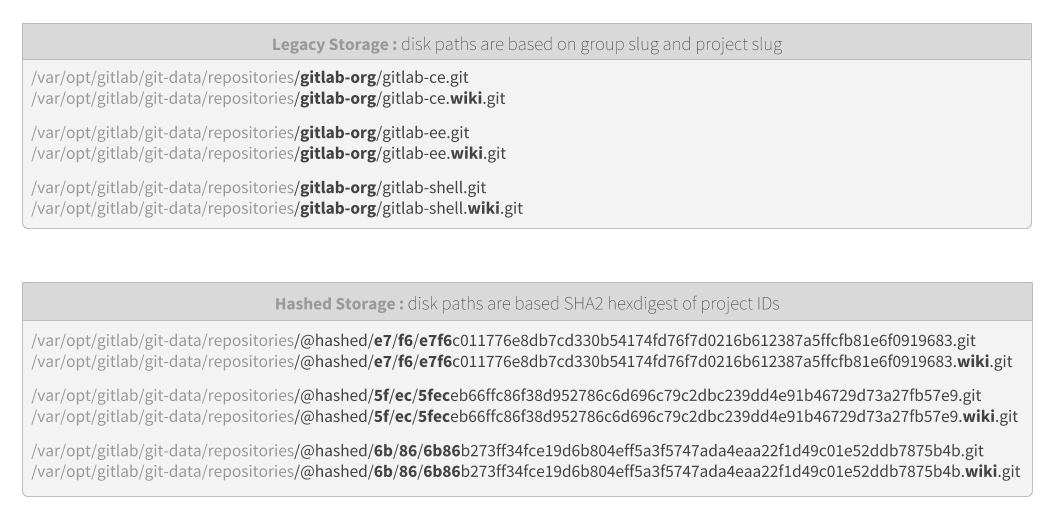

While still working in Phase 3, we discovered another major limitation around how we stored files on disk. GitLab, for historical reasons, stored repositories and file attachments in a similar disk structure as the base URL routes. For group and project gitlab-org/gitlab-ce there would be a path on disk that would include gitlab-org/gitlab-ce as part of it. The same is true for file attachments.

Keeping both the database and disk in sync, even not considering Geo replication, means that at any time a project is renamed, several things have to be renamed on disk as well.

This is not only slow and error prone: what should we do if something fails to rename in the middle of the "transaction?" This is also problematic when replication comes into place as we are susceptible again to processing it in the correct order or risk a temporarily inconsistent state.

We tried to find a solution to problems around the order of execution of the events and we came up with three ideas:

- Find or build a queue system that is guaranteed to process things in the same order they were scheduled

- Detect and recover from any replication failure or data corruption

- Make every replication operation idempotent, removing the queue-ordering requirement completely

The first one was easily ruled out, as even if we switched to a queue system with that type of guarantee, it would be either slow due to the lack of parallelism in order to guarantee the order requirement, or will be extremely complex and hard to use as it would require extra care to have the same guarantees while also working in parallel.

We found no system that satisfied our needs, and even if we considered a standalone queue solution, we would lose the Postgres advantage from the previous generation, of having both the main database and the queue system always in sync.

Ruling out the first one, we considered the second idea of detecting and recovering from failures and data corruption as we concluded we needed it for Disaster Recovery anyway. Any robust Disaster Recovery solution needs to guarantee that the data it is holding is the exact one it's supposed to have. If, for any reason, that data gets corrupt or someone removes it from disk, it needs a way of detecting it and restores it to the desired state.

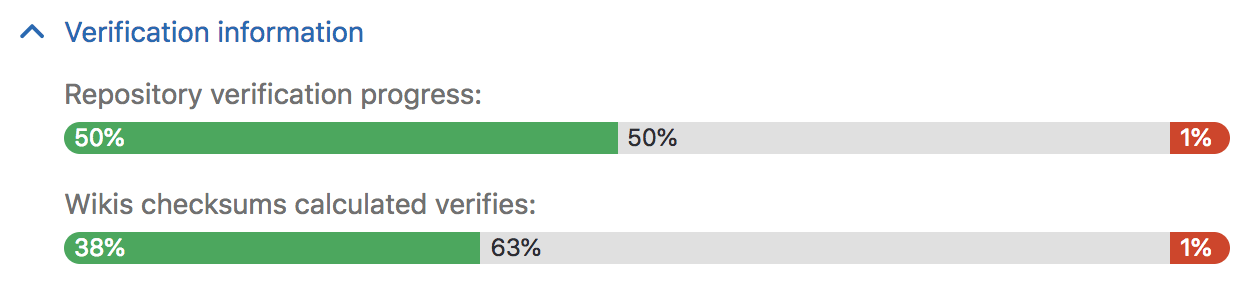

To achieve that, we built a robust verification mechanism that generates a checksum of the state of the repository and is stored in a separate table in the primary node. That table gets replicated to secondary nodes, where another checksum is also calculated (and stored in the Tracking Database). If both checksums match, we know the data is consistent. The checksum is recalculated automatically when an update event is processed, but can also be triggered manually.

We used that mechanism to validate all repositories in gitlab.com when successfully migrating from Azure to GCP, last month.

The verification mechanism is not enough and while it gives us the guarantees we need, we can do better, which is why we also decided to implement the third idea as well, and make every replication operation idempotent in order to remove any situation where processing the incorrect order of events would put data in a temporarily inconsistent state.

We are calling that solution the Hashed Storage. This is a complete rewrite of how GitLab stores files on disk. Instead of reusing the same paths as present in the URLs, we use the internal IDs to create a hash instead and derive the disk path from that hash. With the Hashed Storage, renaming a project or moving it to a new group requires only the database operations to be persisted, as the location on disk never changes.

By making the paths on disk immutable and non-conflicting, any create, move or remove operations can happen in any order, and they will never put the system in an inconsistent state. Also replicating a project rename or moving a project from one group/owner to another will require only the database change to be propagated to take full effect on a secondary node.

What to expect from Geo in the near future

Implementing Geo has been an important effort at GitLab that involved many different areas. It is a crucial infrastructure feature that allowed us to migrate from one cloud provider to another. We also believe it's an important component to support the needs of many organizations today, from providing peace of mind regarding data safety in the events of a Disaster Recovery, to easing the burdens of distributed teams across the globe.

We've been using the feature ourselves and this allowed us to stress-test the biggest and most challenging GitLab installation, GitLab.com, making sure it will work just as fine for any other customer.

Over the upcoming months we will be focusing on the following items:

- Release a push proxy for Geo secondary nodes: Pull and push from the same remote transparently

- Release Hashed Storage as Generally Available

- Improve configuration: We want to reduce the steps and make it simpler via automating most steps

- Improve the verification step: Improve the signals we use for the checksum

- Improve the Geo UX and UI

- Keep improving performance and reliability

- Support replication of GitLab Pages and the internal Docker Registry